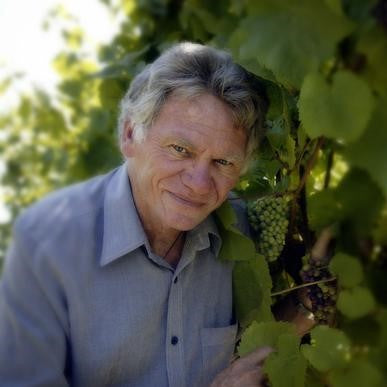

The ‘Flying Vine Doctor’ Richard Smart has been involved with worldwide viticulture since the mid 1960s dating to time spent at Roseworthy College in his native Australia where he once served as its Faculty Dean for Oenology, later as Government Viticultural Scientist in New Zealand where he helped to lay the groundwork for its quality-oriented and internationally competitive wine industry. Author or co-author of over 380 publications including his acclaimed book “Sunlight into Wine”, he’s served as Viticultural Editor and a principal contributor to Jancis Robinson MW’s The Oxford Companion To Wine (1994, 1999 and 2006). Since the mid-80s Dr. Smart has been involved in international consulting with it being his full time occupation since the founding of Smart Viticultural Services in 1990, during which he’s consulted to over 300 clients, much of which is based upon his widely-admired developments in the field of canopy management, the most notable of which he shares with the Oregon vigneron Scott Henry in the famous training system which bears their names.

During our pre-interview chats you indicated that Charles Darwin's work had an indirect effect in solving the scourge of phylloxera; how so?

It fits in with his book on the evolution of the species and natural selection. It was a no-brainer; once it was realized that the phylloxera insect was causing the damage and that it was indigenous to the US, researchers at the time quickly realized there were native American vine species there that were tolerant of phylloxera. There were several expeditions of French viticulturists who brought back vitis riparia and other cuttings from the US northeast to the calcareous soils of the south of France. In 1875 Pierre Viala went to meet Munson in Denison Texas who had a passion for American varieties and ampelography. He pointed Viala to species that were tolerant of calcareous soils such as those that exist in southern France. These samples were sent to France for grafting and for breeding, producing many of today's rootstock varieties.

Of the many places you've visited, all the clients you've serviced, which has proved the most challenging and why?

Probably my native Australia of which I've written twice. For the last 30 or so years Australian viticultural practices have been dominated by cost saving, so it's no coincidence that mechanical and minimal pruning techniques were developed there along with machine harvesting becoming prevalent. These practices were employed in some of the premium regions so there wasn't an equivalent approach to using canopy management practices that I developed because they were seen as costing more. That they were able to produce better quality disregarded, making it frustrating for me. The Australian wine sector is suffering for this in that vineyard cost-cutting has pushed it to perform in the bulk wine arena.

With nearly 50 years of experience in your specific area of research and work you've a singular opportunity to share with the world your perspectives on the changes you've witnessed. Please tell our readers what your sagacious gaze has noticed of the effects of changing climate.

Anyone who ignores climate change is foolish. The world's wine growers will potentially be one of the most affected groups of agriculturists because of the strong interaction between temperature and variety. By the end of the 21st century there will be great changes. Bordeaux will be comparable to present climates of southern France, an area which does't make the best Cabernet sauvignon nor Merlot. There are enough measurements now showing these changes to be real. I've done some calculations for Australia, and the impact will be substantial as many grapes are now already grown in the hotter regions. With change of climate these areas will become like those too hot to grow grapes at all. The area most susceptible to climate change is the southern Mediterranean, especially Spain. Those such as Tasmania, New Zealand, and Argentina which are effected more by the Antarctica current will show less impact.

Last year I twice visited China's burgeoning Ningxia wine region, finding it…complicated…to say the least. What's your view of Chinese viticulture overall and, presuming you've been there, of Ningxia in particular?

I know Ningxia very well having consulted there the past eight years. I think China has an enormous potential for viticulture. They've considerable land resources with good water resources. The soils are often quite good being light textured and gravelly. Ningxia has an area of thousands of hectares akin to New Zealand's Gimblett Gravels far enough away from the monsoon-effected part of the country; the winter cold here is worse so vines must be buried. They are learning very quickly, have enormous academic training facilities, I believe they'll become a major force in the next 50 years especially since it can shift its plantings north to avoid incurring the deleterious effects of climate change. But they've some technological issues to overcome.

The lauding of winemakers, or 'vinifiers', over viticulturists to the point of celebrity is now so commonplace as to be a bedrock of the international wine sector, at least in regards to its marketing; why do you reckon this has occurred?

People with ego problems are often attracted to winemaking because of wine's reputation. It's a fault of the English language that we have 'wine makers' but not 'grape makers'. The concept that there's someone who 'makes' wine is nonsense; an enologist is someone who guides chemical and biological processes that result in wine while a viticulturalist essentially guides biological procedures to make grapes.

You're probably best known for your work with vine canopy management. What are some of the more recent developments in this area yet to be widely recognized?

The Smart Dyson system has its adherents around the world, particularly in South Africa. The principles in the book aren't widely used aside from California and some other parts of the US. I have a client in New Zealand with more Scott Henry-trained vines than anyone else in the world because they find it works so well, giving better quality grapes and wines. Sadly many people haven't made the effort to properly evaluate canopy management. The cost-saving culture has kept this from spreading further coupled with a lack of concern for quality. Irrigation management and canopy management are the two principal ways of improving wine quality in the vineyard. One of my passions now is on grapevine trunk diseases, I had eutypa on the vineyards I owned in the Barossa Valley, something that's become a great problem around the world and what I see as the biggest threat currently. It's typically misunderstood, poorly recognized, and not always treated. I'm sure it'll be overcome during the next decade but I don't know anywhere in the world currently where nurseries aren't producing diseased vines for sale.

On a basically comprehended level how might your Homoclime analyses be utilized by the sommelier in assessing a wine?

Since climate has a major impact on wine styles, we might expect similar wine styles from similar homoclimes. However, we need to remember that many other factors affect wine style, like year to year variation in climate, vineyard management etc, so do not look for too much similarity. Homoclimes are a useful guide as to which varieties might do well in new wine regions; similarity of wine styles can be made between wines from similar climates. For example, you've homoclimes found both in New Zealand and California.

It's been a long while since the publication of "Sunlight Into Wine". Have you another book in the works?

'Sunlight Into Chinese Wine' is the book I'm now working with Chinese co-authors to be published at the end of 2016.

To what extent is your pure enjoyment of wine informed by your extensive knowledge of how it originated?

I'm fascinated by the biology of grape and wine production, to drink wine is fulfillment of some of that. I'm also intrigued by its essential complexity--different styles and different varieties though this has grown into some nonsense due to the California foundation of varietal labeling. Recent statistics show that we're planting more of fewer varieties, what I call the 'Coca-Cola'-ization of wine. It seems sad to me that the diversity of wines which can be produced by different varieties is denied to wine consumers.

Learn more about viticulture in our Viticulture & Enology Workshop.

Check out our full schedule of programs, workshops and public events. Private, customized experiences and corporate training is also available.