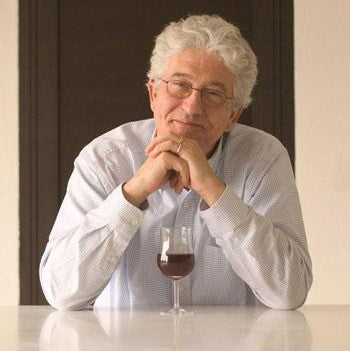

The veteran Burgundian winemaker of Louis Jadot and relative newcomer to Oregon's Willamette Valley with its Résonance brand has long been an advocate of sensible winemaking whether manifested in biodynamic viticulture & winemaking or merely in the expression of quality in varying means--no less via his unbridled enthusiasm for life and wine. My latest encounter with Jacques Lardière was at the centerpiece salmon dinner of last summer's International Pinot Noir Conference with his compatriot Thibault Gagey, seated next from us. When abruptly approached by a Coloradan wine lover asking if there's a difference between wines of Burgundy and Oregon, Lardière responded with his typical geniality rather than display unease. With no questions prepared we, needless to say, managed a buoyant time.

How do you describe the confluence of ambient yeasts in creating wines in both Burgundy and Willamette?

It's difficult to delineate because the applied research is incomplete, but when we're unable to answer completely that can be good. What I can say is that I've no idea with the strains I've to work with in Oregon. It could be another level. I can inoculate Burgundy yeasts in an effort to make an Oregon wine seem more like a Burgundy wine, or I can do the reverse. If you use a little bit of 'starter' yeasts for a wine it can make a big difference. When fermentation starts we may have one strain dominating when later another may take hold. For us we use natural yeasts because it works. If I've a problem in having no ambient yeasts I'd be crazy then not to inoculate a little bit. But the less we do, the better. The yeasts act upon ripe berries they help it release macro-molecules which enable it to continue while increasing the replication of more yeasts, creating an agility in the process that helps it to achieve its own balance. The molecules will then be free to find their way in expressing themselves naturally; each has its own vibration.

A decade ago a Burgundy university asked to study my yeasts and wines because they wanted to check on how we made our wines, only to come back offering to sell me yeasts to make my wines that were selected from those naturally occurring!

For your Résonance project in Oregon, to ensure a stable yeasts population, are you cultivating what you already have?

We are organic, biodynamic until 2011 though I hope we return to it. I am confident in what we have naturally; it's very interesting, there's no problem. Why would you want to change something that's already successful? A good winemaker are guys who accept what is natural and do nothing. Of course if we've a mistake then we have to do whatever we can to make a wine be good, but better to do this before a mistake is even made! The most critical situation for winemakers are when they're too stressed, too judgmental of the work they do. 'If you cut a flower then you move a star.'

Have you planted Chardonnay at R

ésonance?

We planted a little having made experimental batches in 2015 and 2016 at a new plantation in Dundee. But we're here for Pinot Noir first.

Have you curiosity for Gamay here?

Why not, I'm sure we'd be able to make a very good Gamay, but not one that'd resemble ones grown on the schist mother rock of Beaujolais. Minerality is the key to producing great wines, chemistry is nothing without this--physics is what we need.

What are some of the greatest experiences you've had with sommeliers?

Too many act formulaically from their schooling. We have a lot of young guys, and younger people too often push what they think is 'right'. It takes time to accept, to digest all that life offers our minds. This is normal. I find they serve too much young wine--it's not their fault because the market demands that.

What thoughts have you for adaptations made in Burgundy to climate change?

What we know is that we have more CO2 in the atmosphere which impacts the maturation of the grapes. We have the warming of the climate making both the day and night temperatures warmer, but the problem is less of cumulative warmth than it is the quality of the light. The question is how we'll work with the grapes in the vineyards. It's the same in the US. It's not evident that we're adapting accurately as the changes are relatively new.

After Burgundy and Willamette, where is the next most exciting place for Pinot Noir?

I spend time in Santa Barbara County where good

Chardonnays and Pinot Noirs are made, and in dry climates. Chile, too, has some good Pinot Noir. We've no project there but the mentality of winemakers there are very interventionist coming from their university training. It'll take 20 years 'unlearning' to change this!